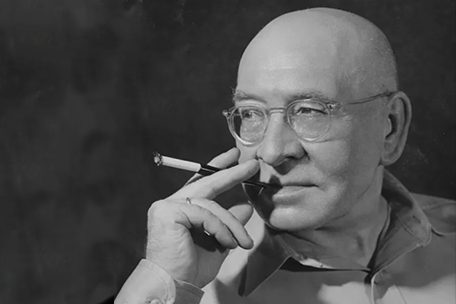

| Alfred Korzybski (1879-1950)How is it that humans have progressed so rapidly in science, mathematics, and engineering, yet we continue to exhibit behaviors that result in misunderstanding, suspicion, bigotry,hatred, and even violence in our dealings with other people and with other cultures?

|

Alfred Korzybski pursued this question as an engineer, military officer, and extraordinary observer of human behavior. He survived the horrific battlegrounds of World War I and wondered why humans could progress and advance in some areas, but not in others. He theorized that the attitudes and methodologies responsible for advancements in engineering, the sciences, and mathematics could be applied to the daily affairs of individuals, and ultimately cultures. He called this new field “general semantics” and introduced it as a practical, teachable system in his 1933 book, Science and Sanity.

Below, find biographical information about Alfred Korzybksi including personal accounts, his oeuvre, his obituary, what others have said about him, as well as audio and video.

Biography of Alfred Korzybski

Highlights

- Born 3 July 1879 in Warsaw, Poland.

- Died 1 March 1950 in Sharon, Connecticut.

- At outbreak of World War I (age 35), volunteered for service in the Second Russian Army; assigned to General Staff Intelligence Department.

- Sustained hip injury when his horse was shot out from under him, as well as surviving a leg wound and internal injuries.

- In December 1915, assigned to Camp Petawawa testing grounds in Canada to observe new artillery tests.

- After collapse of the Russian army and the revolution of 1917, joined the French-Polish army for the duration of the war. Also assisted the U.S. government by lecturing on behalf of the war effort to sell Liberty Bonds.

- In 1919, met and married Mira Edgerly, an accomplished portrait painter.

- In 1921, completed and published Manhood of Humanity.

- Devised the Structural Differential model (originally called the Anthropometer) and applied for U.S. patent in 1923.

- Presented and published Time-Binding: The General Theory in 1924 to the International Mathematical Congress in Toronto.

- Under guidance of Dr. William Alanson White, spent two years observing and studying mental illnesses and treatments at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, D.C.

- Completed and published his second book in October 1933, Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics (originally titled Time-Binding, The General Theory: An Introduction to Humanology).

- From 1934-1937, traveled around the country giving public and private seminars based on the methodology of general semantics as formulated and discussed in Science and Sanity. Some of the more significant seminar venues included Harvard University, Williams College in California, Olivet College in Michigan, the Barstow School for Girls in Kansas City, and several conducted in Los Angeles.

- In August 1938, after securing initial funding from Cornelius Crane (Chicago) and Frances Stone Dewing (Massachusetts), founded the Institute of General Semantics in Chicago. He was assisted by M. Kendig who resigned as Headmistress of the Barstow School to move to Chicago and become the Institute’s first Education Director.

- Began regular schedule of delivering seminars at the Institute and various universities throughout the country.

- With the Institute, moved to Lakeville (Lime Rock), Connecticut, in April 1946 following the post-war housing shortage in Chicago.

- Continued his exhaustive schedule of seminars until his death on 1 March 1950.

- His final paper, “The Role of Language in the Perceptual Processes” was published as a chapter in Perception: An Approach to Personality, edited by Robert R. Blake and Glenn V. Ramsey in 1951.

Accounts of Alfred Korzybski

-

Read “Alfred Habdank Skarbek Korzybski: A Biographical Sketch” by Korzybski’s long-time literary secretary and executrix Charlotte Schuchardt Read.

-

Read “Alfred Korzybski: A Memoir” by Korzybski’s long-time associate and IGS Education Director M. Kendig.

Published Works

The following are the published works of Alfred Korzybski:

- Manhood of Humanity

- Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics

- Olivet College Lectures

- Collected Writings

Audio & Video

Kenneth S. Keyes, Jr. — a student of Alfred Korzybski and one might call a documentarian of the man — filmed Alfred Korzybski in 1944 at the Institute of General Semantics in Chicago, Illinois, and in 1947 in Warm Springs, Georgia (9:23).

A short video with Korzybski explaining the process of abstracting using his Structural Differential model (2:50).

New York Times Obituary

Click here to access the page on the New York Times website.A.H. KORZYBSKI, 70, SCIENTIST, IS DEAD

Founder of General Semantics Institute Saw Ideas Put to Use in Many Fields

SHARON, Conn., March 1 (AP) – Alfred Habdank Korzybski, scientist and author, an early authority on general semantics, died early today at Sharon Hospital at the age of 70. Death was due to a coronary thrombosis, with which he was stricken at his home in near-by Salisbury shortly after midnight.

Surviving is his widow, Mira Edgerly Korzybski of Chicago, a portrait painter, whom he married in 1919.

A pioneer in semantics, Mr. Korzybski founded a new school of psychological-philosophical semantics which he named general semantics. He had hundreds of followers throughout the world and was consulted by many scientists and scholars. Widely credited with having expanded semantics from its ordinary concern with only the meaning of words in a new system of understanding human behavior, Mr. Korzybski held the conviction that “in the old construction of language, you cannot talk sense.”

The scientist contended that because of Aristotelian thinking habits, which he thought outmoded, men did not properly evaluate the world they talked about and that, in consequence, words had lost their accuracy as expressions of ideas, if ever they had such accuracy. He explained that life was composed of non-verbal facts, each differing from another and each forever changing. Too often, he contended, men got the steps of their thought-speech processes confused, so that they spoke before observing and then reacted to their own remarks as if they were fact itself. As Mr. Korzybski explained it, general semantics had to do with living, thinking, speaking and the whole realm of human experience.

His theory was put to practical use in the fields of public, industrial and race relations and everywhere that misunderstanding among people is due to different values and structures of words.

In explaining simply what he meant by misleading words, Mr. Korzybski said that to say a rose “is” red is a delusion because the red color was only the vibration of light waves. In 1938 Mr. Korzybski found the Institute of General Semantics in Chicago. In 1946 he moved the institute, of which he was president and the director, to Lakeville, Conn.

His book, Manhood of Humanity – The Science and Art of Human Engineering, which appeared in 1921, caused a stir in the intellectual world, as did his second book, Science and Sanity, An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics, 1933.

Descended from a long line of engineers, mathematicians and philosophers, Mr. Korzybski, who was born in Poland, was a Count before his American naturalization. He attended the Warsaw Polytechnic Institute, managed his family’s estate and taught mathematics, physics, French and German in Warsaw before World War I. During that conflict he was twice wounded and served on the Russian General Staff before being sent to this country and Canada on a military mission.

In 1918 he was a recruiting officer in the United States and Canada for a Polish-French Army, and a war lecturer for our Government. Mr. Korzyski served, in 1920, with the Polish Commission to the League of Nations. He had lived in New York at one time.

What Others Have Said

Irving J. Lee

He deepened my awareness of the human relevance of all studies. He has too vividly shown that what men say and do is inevitably linked with what they see and with what they assume. Accompanying that insight is a new kind of respect for human potentiality.

J. Samuel Bois

… he turns your attention to something less tangible, something that you cannot compute additively, that you cannot demonstrate to others with a brilliant display of ‘whys’ and ‘therefores’. He makes you conscious of structure, relations and order. He helps you feel that you as a living-thinking-feeling-acting individual are a conscious node of interrelatedness in a universe that you eventually feel throbbing with you, through you, around you …

Douglas M. Kelley

He existed as a process and produced in his lifetime a number of ink marks presenting to some degree his basic formulations of the function of mankind. In this capacity, he was never surpassed. His time-binding theory and his subsequent development of General Semantics as a method for the achievement of its maximal function severed across old lines of thought as does a clean cleaver through moldy cheese. This cleavage has yielded a resultant new approach, which is only beginning to be felt in multiple scientific disciplines.

Guthrie Janssen

… [his] was not the sentimental approach, nor the metaphysical, which have had such a long vogue. Rather it was an engineering approach. He began with an ‘obvious’ fact, but one so large that it had mostly been taken for granted and never adequately explored before; namely, that humans represent a symbol-producing, symbol-using class of life. In other words, the arrangements by which we regulate our lives and the relationships among us are established through the functioning of our symbol systems. Man has created for himself an environment of symbols, and for better or for worse he has to live with them.

Alfred Habdank Skarbek Korzybski:

A Biographical Sketch

by Charlotte Schuchardt Read

Records concerning Korzybski’s life prior to his coming to this country in 1915 are, as far as I know, practically non-existent. He did not write diaries and kept other records later only in relation to his work. The data given here are derived from biographical information Korzybski had related to his students at various times, from a few war documents, from his wife, Mira Edgerly Korzybska, and my own observations since my first seminar in 1936 and working with him at the Institute since 1939.

— Charlotte Schuchardt Read

Born Into A World In Flux

The world into which Alfred Korzybski was born on July 3, 1879, in Warsaw, Poland, was stirring under the weight of oppressions, and the impacts of new outlooks. Repeated partitions of Poland by the Austrians, Prussians am Russians had only intensified the nationalistic feelings of the Poles, and in Warsaw they were chafing under the rule of Czar Alexander II; Emperor Franz Joseph in Vienna was reigning over his Hapsburg Empire; the philosophies of Kant, Fichte and Hegel had seeped into the fabric of German life and. were greatly influencing Western cultures; fired by Marx and Engels, workers were rebelliously, surreptitiously, banding together; only twenty years earlier Darwin’s Origin of Species had begun a storm of controversy in England; and there was feverish activity in science, as a revolutionary new era led by Faraday, Bunsen, Maxwell, etc., was breaking ground and laying the foundations for the even greater discoveries to come.

Alfred Vladislavovich Habdank Skarbek Korzybski was the son of (Nobleman) Ladislas Korzybski and (Countess) Helena Rzewuska. His father was an admirer of British customs, hence the name ‘Alfred’. The Habdanks or Skarbeks, his father’s family, were one of the original Polish comites (from the Latin comes: overseer, teacher . . . scholar, noble youth, etc. . . . one of the imperial court). The legend about the origin of this family name goes back some four centuries to the time when there was a problem of war or peace between a German prince and a Polish prince. One of his ancestors was sent as an envoy to the German prince, who arrogantly took him underground and, showing him a vault of gold, said, ‘With this we will beat you.’ The envoy replied by taking his ring off his finger, flinging it into a barrel of gold, and saying, ‘Go gold to gold, we will beat you with iron!’ The German prince was amazed and said ‘thank you’ (habe dank). When the Polish envoy returned to Poland and that gesture became known, he was given the name ‘Skarbek’ {‘skarb’, ‘treasure’), with the crest ‘Habdank’, a flattened barrel. A war followed and the Poles won.

The Surname of Korzybski is derived from the name of the estate of Korzybie, the suffix ‘ski’ being comparable to ‘of, or the French ‘de’.

Alfred Korzybski was the second child in the family, and the nursery had already been established for his sister, about two years older. As a baby, he was unusually quiet. ‘My friends will never believe me today, but I was born silent,’ he used to say. ‘I didn’t cry; I just looked around.’ For half of each day there was a French governess, for the other half a German governess. Learning these two languages, besides Russian, used in all public places, and Polish, taught in schools in the Russian language, was significant to him in his later work. There were no other children in the family, and according to the prevailing custom, the son of the gardener was chosen as a playmate. Alfred had no toys except tools, or bits of material that he found and made into playthings. He watched the blacksmiths, the horses, the cattle and the workers on the family country estate of Korzybie near Warsaw. He accompanied his mother when she traveled to the baths of Europe – Karlsbad, Franzenbad, etc. When he was five years old, his father, an engineer with the rank of General in the Ministry of Communication, and a lover of mathematics and physics, gave him the feel of the differential calculus, of the latest scientific discoveries, etc., and the mathematical way of thinking, an outlook which was so profoundly to influence his life.

Farming

Korzybie was considered a model farm, to which the United States Department of Agriculture sent representatives for study. His father had devised new methods of agriculture, contour plowing, irrigation systems, etc., and had written a book on ‘Agricultural Amelioration’. That part of Poland (‘flatland’) was agriculturally handicapped by a cold clay undersoil. The tax imposed by the Russian government on the landed aristocracy, paid in this case in potato alcohol, was such that the estate had to be carefully and penuriously managed – each potato mattered, each pig or hide of a cow. With his father often at the Court in St. Petersburg (now Leningrad) or traveling, young Alfred had to assume the duties of supervising the farming activities. The peasants loved the ‘little master’ (‘golden hands’ some called him). He in turn looked after them, advised them, was their ‘doctor’ when there was no medical help available for many hours, etc.

At harvest time soldiers from nomadic tribes, Cossaks, etc., and the various areas of Czarist Russia were hired to help, and in his school uniform he learned how to handle them under stern discipline, gaining also some insight into the psychology of socio-cultural differences.

Schoolwork

While attending school he seldom studied his homework, but sat in the front row listening attentively to what the teacher had to say, trying to grasp the subject as a whole. At his father’s urging he was trained as a chemical engineer at the Polytechnic Institute in Warsaw. But privately he developed an interest in law, mathematics, and physics instead, then found, too late, that he could not enter a university to pursue a career in such fields because his previous curriculum. in the Realschule did not include the prerequisites of Greek, Latin, etc. This was an intense disappointment and frustration to him. In the meantime he read constantly in the subjects of his special interests, including the philosophies of the day and of history, history of cultures and of science, comparative religions, the literatures of Poland, Russia, France, Germany, etc., each in their respective languages. At one time he taught mathematics, physics, French and German at a gymnasium in Warsaw.

Traveling as an eclectic scholar in Germany and Italy, he spent the major portion of this time in Rome and its university. He became friends with some of the Cardinals and others connected with the Vatican during the time of Pope Leo XIII. It was there, in his early twenties, before the Cardinals and the General of the Jesuits, that he made his first and only speech before coming to this country – on “The Relationship of the Polish Youth toward the Clergy, and the Clergy toward Polish Youth.”

During these years of study, managing the estate, and an apartment house which his family owned in Warsaw, he was looking into the life surrounding him, continuously seeking to comprehend what he saw, felt or read about. He was armed with an analytical attitude which his father had conveyed to him in his explanations of scientific discoveries. He watched the men, women and children wherever he went; he learned from training and caring for his horses, which he loved, and from his English bulldog ‘Taft’, named after President William Howard Taft.

While traveling he rode third class, eating his dark bread and garlic together with the laborers and others by whom he was surrounded. When he came to a strange city he found an inexpensive room, secured a map and studied it. Then he took long rides through the town, roamed through the slums, ate his sandwich at the aristocratic cafes (for he had little money to spend), and studied how the different people lived.

In the meantime he was participating eagerly in gaiety and mischief with his classmates and friends, swinging the ladies vigorously as he twirled to the waltzes, wrestling, riding, swimming, singing his favorite operatic arias in his resonant bass. In Rome, where he became involved in the romantic affairs of the Italian court, he fenced expertly in duels and was called the ‘Maladetto Polacco’. He was generally the ‘life of the party’, but privately he was chiefly interested in reading and studying in his spare time. In their troubles, his friends came to him for advice, in their need for counsel the peasants sought his aid, at home he was the mediator for the household servants.

Returning from the City

When he returned from Rome he was shocked with the realization that his former playmate, the gardener’ s son, as well as all the other peasants, could neither read nor write, yet their labor had for generations earned the money for the education and the freedom to travel of their landowners. He found release for his reactions against this injustice by building a small schoolhouse for the peasants on the country estate. It was against the Czarist law, however, to educate the peasants, who were deliberately kept illiterate. He was sentenced to Siberia, but his father had the sentence suspended .

From photographs and his own descriptions of those days, he appeared to have been rather thin, broad-shouldered and muscular, of medium height, with blue, alert, contemplative eyes, his hair very blond, and at times he grew a mustache which he habitually twirled up at its ends.

At the outbreak of the First World War, when Korzybski was 35, he volunteered for service in the Second Russian Army, am was assigned to a special Cavalry Detachment of the General Staff Intelligence Department. He became the chief assistant to Colonel Terechoff, who in turn was close to Grand Duke Nicholas, the Imperial Commander. This Second Army was the key army of the Eastern Front. It fought (and lost) the battles of Warsaw and Lódz, and was practically annihilated when it was sacrificed in an attack on the Germans at the Masurian Lakes of East Prussia, to divert the German divisions from taking Paris. Korzybski was the representative of the Second Army Intelligence Department on the battlefields, dealing with the generals or about a half dozen of the Russian armies, concerned with espionage and counter-espionage, predicting the German movements, interviewing prisoners, etc. Under the weight of his horse as it was shot and fell on him, his left hip was severely dislocated; at another time he was shot in the knee, and, again, in the panic of the battle of Lódz, when a cannon was obstructing the road of retreat he cleared it out of the mud himself and endured lasting internal injuries.

In The Great War

Immersed as he was in sufferings on the battlefronts, intimately at home with death and pain, contemplating the thousands of years of such continually recurring conflicts and their attendant human tragedies, his questioning became focussed on: ‘Why? What is wrong? How can this be prevented?’ He had no answer.

In July, 1915, he was ordered ‘At the Disposal of the Minister of War’, and sent to Petrograd, where he was assigned to the Bodyguard Heavy Artillery. In December, 1915, he was sent to Canada and the United States as an Artillery Expert of the Russian Army. His title: Inspector of the Commission for the Acceptance of the Orders of the Artillery Department. ‘I knew nothing about artillery except from the receiving end,’ he used to say. But at the proving grounds of Petawawa Camp In the Canadian forests he spent, his spare time until late at night mastering the technicalities of his assignment, and from newspapers studied English for the first time.

When that proving ground disbanded, in February 1917, he went to New York, where he supervised the loading of ammunition in New York Harbor. He then became the Chief Inspector of a horseshoe factory in Erie, Pennsylvania, where he reorganized its management to bring about greater efficiency and speed in the production.

With the collapse of the Russian Army and the Revolution in 1917, he was ordered to return to Russia. He preferred, however, as did many other Poles, to join the French-Polish Army which was being formed here, in order to continue in the war with the Allies. He was appointed Secretary of the French-Polish Military Commission and, later, Recruiting officer for the states of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. With little sleep or time to eat, with scarcely enough army funds to buy postage stamps for his recruiting work, he became more and more haggard and exhausted.

Lecturing

Documents concerning these varied war duties mention his ‘honesty, conscientiousness, energy and zeal’, and stress that he was ‘very deeply devoted and interested in the work entrusted to him . . . in the highest degree a lover of work.’

The United States Government sought his services as a War Lecturer to increase the sale of Liberty Bonds and speed up production. In this capacity he traveled throughout the southern states, speaking in five or more different languages, depending upon the nationality of the local foreign groups. ‘How he speaks such understandable and graphic English, how he remembers facts and figures so accurately, how he imparts so much information usually considered dry in such an attractive manner and keeps the breathless attention of his large audience for so long a time is difficult to comprehend. . . . He is a hard worker and is willing apparently to go a pace that would kill an ordinary man. . . . His speech was direct, forceful and most compelling. The language used was most diversified and Mr. Korzybski held his audience spellbound in rapt and undivided attention from start to finish. It is rarely that I have had the pleasure of listening to such an appeal, or so brilliant an account of the great war. His work will do great good.’ These are quotations from letters to governmental officials about his lecturing. During part of this time he was also a Labor Inspector in coal mines, and later was ordered by the Government to attend the Pan American Congress of Labor at Laredo, Texas.

These troubled years intensified his urge to understand, and with the Armistice there was no release from the relentlessly prodding ‘why’. Now and then some moving experience stung him into a heightened awareness of the problem, such as when he had looked down from the top of a skyscraper (the Woolworth Building) on the seething city of New York, on the panorama of human achievements, the tiny human beings ‘crawling’ below, and felt pressed to ask himself again, ‘How could this have been done?’ Still he had no answer.

In Washington, D. C., shortly after the Armistice, he met Mira Edgerly, an American of wide fame as a portrait painter on ivory. Having painted in the British Isles and on the European continent, as well as throughout this country, her list resembled an international social register. Because of her own interest in people and concern for how they happened to get ‘that way’, she recognized in Korzybski those qualities for which she had been looking in her search for a husband. ‘I had never met anyone with such a capacity to care for humanity-as-a-whole, as few men are capable of caring for one woman,’ she said later. They were married in January, 1919, and for her ‘incomparably inspiring help and valuable criticism,’ ‘her whole-hearted and steady support, and her relentless encouragement,’ he expressed his grateful appreciation in the prefaces of his books which, he has said, would not otherwise have been written.

‘What makes human beings human?’ The endless questioning continued. With his mathematical training he realized eventually that his question must be reduced to the simplest, most encompassing, functional terms. Taking into consideration all living organisms, he asked himself, ‘What is the role of plants in this world? What do they do?’ He found they chemically synthesize the soil, water and air with solar energy. ‘What of the role of a dog, a horse, or a monkey?’ Their survival depends on moving around in space. ‘We cannot deny them communication. Nor can we deny them “intelligence” or “emotion”. Their devotion! Often they are more faithful, more dutiful than many humans. What about humans? How do they differ?’ The question was deeply disturbing.

One night he suddenly sat up in bed with tears dripping off his chin, so moved that he had finally solved his question in his sleep. ‘Humans have the capacity to transmit from generation to generation; one generation or one person can begin where the other left off,’ he said to his wife. ‘Man is not an animal.’ He did not have the terms then, he had had to analyze first what the different classes of life DO. Shortly, he formulated the labels – ‘chemistry-binding’ for plants, ‘space-binding’ for animals, and ‘time-binding’ for that characteristic, defining capacity, out of all life, unique in human beings. With this simple functional formulation he could at last become articulate.

Seclusion In Missouri

To be free to work it out, he sought seclusion on his sister-in-law’s Missouri farm far from the interruptions of a demanding social life. But when he tried to concentrate on his new problem, he found that he could not, for other feelings welled up into consciousness. The memory of the oppressions which had been such a part of his youth and milieu still boiled within him. Some of his ancestors had had to walk the long, bitter-cold road to Siberia, and a gallows still stood symbolically on Korzybie. For ten days he had to let his pent-up feelings of rebellion burst and spill out in vilification on paper. Only after he had ‘purged’ himself of these feelings did he find it possible to settle down to his new task, which yet involved the old in wider perspective.

With his two fore-fingers bandaged after they had become inflamed and split with the typing, he picked out on an old ‘thrashing-machine’ typewriter the first draft of Manhood of Humanity: The Science and Art of Human Engineering. In that book he expounded and developed his new analytic functional definition of ‘man’ as a ‘time-binding class of life’ – and the implications of this for humanity, anywhere.

He took this crude manuscript, written in a language new to him, to the outstanding mathematical philosopher, Professor Cassius Jackson Keyser, Adrian Professor of Mathematics at Columbia University. Professor Keyser had been working on his Mathematical Philosophy for many years and had planned to finish it during his sabbatical year. When he read the manuscript of Manhood of Humanity he found that Korzybski had made a formulation which turned out to be the kernel he himself had been searching for, circling around, all those years. Then, instead of completing his own book that year, he spent his time helping to edit Korzybski’s manuscript, and made that new notion of man and its potential consequences the thesis of his address to the Phi Beta Kappa Society in May, 1921.

Manhood of Humanity was published early in 1921, and the first printing was sold out in six weeks. ‘The best book of the century . . . the most useful,’ some reviewers acclaimed. ‘Epoch-making . . . A mathematical theory which may revolutionize world thought in every field . . . . A more daring theory than Einstein’s.’ It was viewed skeptically by others with ‘Fine, but what of it?’ Yet whatever their views, none could help but wonder at the courage of this one man who, single-handed, without institutional backing, traveled and lectured on his new theory, or be amazed at the untiring energy and tenacity with which he pressed on alone, demanding no less than a revision to the roots of our ways of thinking about ourselves.

The Idea of Time Binding

But – how do we humans ‘bind time’? What are the neurological mechanisms? How do they function? He had a feeling that his formulation was somehow very important; where it would lead he did not know. He felt he must investigate it further. This required a study of mathematical foundations, mathematics, physics, anthropology, biology, colloidal chemistry, neurology, etc. His circle of friends became wide, including especially the leading scientists in the eastern universities. Part of the summer and fall of 1921 he was the guest of the biologist William E. Ritter, who had been instrumental in the establishment of the Scripps Institution for Biological Research at La Jolla, California.

Later, one day in New York Korzybski was lecturing at the New School for Social Research. There, under challenging personal circumstances, in his urge to convey the difference between animals and humans, suddenly his whole theory coalesced into visual form as he rapidly drew on the blackboard a diagram of the ‘time-binding differential’ or ‘anthropometer’ (the measure of man). This was later named the ‘Structural Differential’, which became so fundamental in his work as a diagrammatic or modelled representation of the premises of his system, and the functioning of the human nervous system as differentiated from that of the animal. Throughout his later writing and lecturing he depended heavily on the use of diagrams. He was exceptionally ‘visual-minded’; his own ‘thinking’ was non-verbal, in visual structural form.

During these times he found relaxation in the use of his hands, and he particularly enjoyed using his Beach-motored electric tools working with leather, metal, and wood. He also devised new methods for Mira Edgerly to protect and work with the large ivories which she used for her unique technique of family group portraiture. Together they made canvas covers for their luggage, reinforced with leather; intricately designed covers for the Structural Differentials, used for travel. In Washington, D. C., they spent many hundreds of hours in the construction of the mahogany models of his Differential.

Korzybski’s first paper after the publication of Manhood of Humanity was ‘Fate and Freedom’ published in the Mathematics Teacher, May, 1923. This was the result of an address delivered before the joint meeting of the Detroit Mathematics and Detroit History Clubs, January 11, 1923; which he also delivered before the Mathematical Club of the University of Illinois, January 12, and at the University of Michigan, January 15. Here he emphasized his heavy obligations to the work of Alfred North Whitehead, Bertrand Russell, Henri Poincarè, Cassius J. Keyser, and Albert Einstein, and we see the beginnings of what was later to grow into his new synthesis to include methodologically all branches of knowledge. ‘In this paper,’ he wrote, ‘I propose to analyze the principles on which the foundation of the Science and Art of Human Engineering must rest if we are ever to have such a Science and Art. . . . it must be mathematical in spirit and in method and if we do not possess methods to apply mathematical thinking to human affairs, such methods must be discovered. Can this be done? …Most of what I have said is hardly so much as a sketchy outline of a vast, coherent system, due, in the main, to the recent work of the few mathematicians before mentioned.’

The other great men from Aristotle to Wittgenstein to whom he felt most indebted as his work progressed are listed in his dedication in Science and Sanity. It is revealing, now, to see the markings, the underlining and marginal comments, in the books in his library which seem to have been influential in the building of his system, selections from which head each chapter in Science and Sanity.

Further Development of His Ideas

By 1924 the main outlines of his second book had already been formulated in the paper he presented on ‘Time-Binding: The General Theory’ at the International Mathematical Congress at Toronto, Canada.

The following two years he studied psychiatric manifestations at St. Elizabeths Hospital, Washington, D.C., with the permission and under the guidance of Dr. William Alanson White, with whom he shared his study of mathematical methods as applied to psychiatry. There he had the freedom to read case histories, to watch and talk with the hospitalized patients. He regularly attended the staff meetings at the hospital and meetings at the psychiatric societies in Washington, discussed papers with Dr. Harry Stack Sullivan and others, etc. Two lectures given by him during this period are published in his second paper on time-binding, which was an elaboration of the first: June 25, 1925 before the Washington Society for Nervous and Mental Diseases, and March 13, 1926 before the Washington Psychopathological Society. In the short bibliography given for this second paper, he made the following classifications: Science, Method; Mathematics, Mathematical Philosophy, Logic; The Theories of Relativity; The Newer Physics; Psychiatry; Miscellaneous; Human Engineering. ‘The material presented here so roughly,’ he wrote, ‘is being worked out in a book form under the title Time-Binding, The General Theory: An Introduction to Humanology.’ The title of this next book, as we now know, was changed to Science and Sanity.

Korzybski then went to Pasadena, California, where in one year he wrote the manuscript of his second book. After that there was the long, tedious labor in Brooklyn, New York, where he elaborated his manuscript, refined it, and attended to all the details of publishing it. During this time, in 1929, he went to Warsaw, Poland, where he presented a summary of his new findings as worked out at that date, at the Mathematical Congress of Slavic Countries.

In December, 1931, he delivered a paper before the American Mathematical Society on ‘A Non-aristotelian System and its Necessity for Rigour in Mathematics and Physics.’ This crisp abstract of his system has been included in Science and Sanity as Supplement III.

Most of the time, however, from 1928 to 1933 was spent at his desk in the large, crowded studio room which was his home in Brooklyn, with almost no help except from his wife and one part-time secretary. There, on the top floor, he and his wife broiled in the summer and froze in the winter. His energy was becoming sapped by the years of blinding, straining toil over manuscripts, checking and rechecking proofs, verifying the formulae with endless patience and precision, specifying to the smallest detail the size and style of type, the layout, the binding, etc. He had added some materials to the original draft, such as the chapter on Colloidal Behavior, the double punctuation standing for ‘etc.’, and such terms as ‘multiordinality’. When the book was already in type he decided to call his work’ general semantics’, and this, and related terms, had to be inserted throughout. Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-aristotelian Systems and General Semantics is a word portrait of his own struggle, the record of the developing of his new system, his ‘spiral’ way of analyzing, and the serious reader must work through it with him to arrive at an understanding of what he tried to convey. After these seven years, worn, haggard and exhausted, with finances depleted, in October 1933 Korzybski and Mira Edgerly finally saw the book off the press.

Lecturing Once Again

‘If it is as important as you say, prove it. Does it actually work?’ This was the inevitable challenge. For, having built this weighty, encompassing, unprecedented, non-aristotelian system, the immensity of which staggered even him, and the inter-relatedness of which caused him to wonder and doubt (he had seen how easy it is to build verbal structures not related to life facts), having checked the soundness of his theory with leading specialists in many- different fields, it remained to be shown what could be done. On this its validity as a methodology lay. He had dismissed metaphysical speculations, [no] matter how wise, as unworkable, and he had proclaimed that physicomathematical methods could be applied with benefit to human living. Did the application of his new methodology influence the evaluations, and so behavior, of human beings? Empirical evidence was the only test. This was the next task to be faced.

Still without institutional backing, he set out alone once more to lecture on his work, now named ‘general semantics’, at the same time training a few serious students for longer periods. In March, 1935, only seventeen months after the publication of Science and Sanity, the First American Congress on General Semantics was held at the Central Washington College of Education, Ellensburg, Washington. He conducted lectures and seminars at the Barstow School, Kansas City; in Berkeley, Los Angeles, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois; Olivet College, Michigan; Harvard University, Marlboro State Hospital, New Jersey, etc., and continued to write scientific papers.

In June, 1938 in Chicago a long-hoped-for goal was realized: Through the efforts of some of his students, particularly Dr. Douglas Gordon Campbell, and with a two-year grant from Mr. Cornelius Crane, an institute was incorporated as the center for training and carrying on his work, with Korzybski as its Director. It was called the Institute of General Semantics, for Linguistic Epistemologic Scientific Research and Education. A long list of distinguished scientists and others who had known him or his work for many years encouraged him by becoming Honorary Trustees of the Institute – Dr. Abraham Brill, David Fairchild, Dr. Clarence Farrar, Earnest Hooton, Dr. Smith Ely Jelliffe, Edward Kasner, Cassius J. Keyser, Dr. Nolan D.C. Lewis, Bronislaw Malinowski, Dr. Adolf Meyer, Dr. Winfred Overholser, Roscoe Pound and many others.

Final Years

The following years were devoted to his Institute, his students, his further writing, etc., and during this time (in 1940) he became a naturalized citizen of the United States. There was continuous pressure of work – the days, evenings, Sundays, and holidays were filled with lecturing, interviewing, writing articles, letters of personal advice to students, long theoretical correspondence with scientists, attending to the office routines, even supervising the most minute details of the care of the large building, at 1234 East 56th Street. There was only occasional relaxation – simple pleasures with students, listening to phonograph recordings, reading detective stories (Joe Archibald was one of the favorites he chuckled over). He often worked during early morning hours, and was reluctant to rest during the day when too weary to go on. He was oblivious to the hours on the clock. There was only the ceaseless driving to finish a piece or writing (an arduous process of many drafts and prolonged ‘delousing’, as he called it, but the creative work which he craved to do); there were the many intensive seminars for 30-50 students, on whom he poured his energies hour after hour, as if it were of utmost importance for each individual to understand, to feel the weight of the world problems, the human values, he dealt with; there was endlessly some student to be seen to try to help (whether he or she wanted it or not). And all the while he was worrying that uncertain finances would not allow the Institute to continue.

By August, 1941, when the Second American Congress on General Semantics was held at the University of Denver, there were already applications in many fields, and his work was being taught in schools and colleges, such as the University of Iowa, University of Denver, Northwestern University, etc.

In 1942 a group of Korzybski’s students in Chicago organized a society, now called the International Society for General Semantics, for the purpose of making his work more widely known and also, originally, to help to support the Institute financially. [In 2004, the International Society and the Institute merged.]

Nothing gave Korzybski greater pleasure than the realization that his work was of help to others, in whatever way, to find how it was applied with benefit in professional or other pursuits – in education, law, medicine, psychiatry, industry, Journalism, governmental and military problems, etc. – and to watch the development of maturity in his students. He was convinced that ‘the man comes before his work,’ and that therefore the study of general semantics naturally begins with the incorporation of its methods in an individual’s own processes of evaluation.

Sometimes in his dealings with people, including students, he had ‘no tact – only contact’, and this with a force which could hurt or repel.

In his private work with students, if he often did not spare their feelings in exposing with relentless vigor their ‘worst’, holding up to them’ the mirror’ of themselves with uncompromising shocking clarity, he also spared no efforts to help them to achieve their ‘best.’ Many were devoted to him, as he was to them, whether their contacts were long or brief. Some, for whom these methods were too disturbing and hard, became antagonistic; some, overcoming their hostilities, realized years later the impact of what he had tried to convey.

World War II

During the Second War it became more and more difficult to secure help to carry on the office for the growing work of the Institute, as the correspondence and complexities increased, and many who had begun to apply his work professionally were serving in the armed forces. He participated vicariously in the war, partly through large correspondence with students, some of whom were carrying Science and Sanity over ‘the Hump’, in Pacific Jungles, etc. He followed the news intently, ‘ lived through’ the tragedies as they unrolled, with their implications. He repeatedly urged the establishment of scientific coordinating boards in the government for consultation on problems of human behavior, to ‘advise how to conserve and prevent the abuse of human nervous systems.’

In August, 1946, when Korzybski was 67, during the acute housing shortage in Chicago, the building rented by the Institute was sold, and it was necessary to move. New headquarters were established in Lakeville, Connecticut. In this location he continued his wide reading, his writing, and conducting of seminars. Here also, Miss M. Kendig, Educational Director and Editor of the Institute since 1938 and Associate Director since 1942, continued to organize the courses and other activities.

But if, by now, the growing acceptance of his work brought some slackening of his need to fight to demonstrate its value for others, some difficulties grew larger than ever. Along with the complexities of moving and resettling in this new environment of a Connecticut countryside he was plunged deeper in distress over the increasing financial crisis of the Institute, as its continuing existence hung in the balance. More than that there were other problems to be met: he had to protest against a number of misrepresentations or distortions of his work by his students, and this was very difficult for him — a most exhausting concern – for it involved conflicts within him between his feelings as a teacher, a friend, and his ‘scientific social conscience’.

The Institute Continues His Work

Due to the voluntary contributions of the Members of the Institute, the tuitions from seminars, and the increasing sale of books and other publications on general semantics, the Institute managed to continue.

By now Korzybski’ s formulations had begun to penetrate in some measure into many fields, through individuals’ applications and writings, study groups, teaching, etc., and Science and Sanity was in increasing demand. If he was ‘to a large degree responsible for much of the development of [applied] anthropology,’ as one anthropologist said in 1942, or if his methods were, as some put it, being ‘bootlegged’ into colleges and universities, etc., the deeper significance of his work was little felt generally. This was, perhaps, partly due to his not emphasizing the general theory out of which it originally grew, the continuity in its development, and its inter-relationships, also partly due to too easy acceptance by many of the verbal formulations only, and of fragmentary glimpses evaluated as the whole, etc.

Turning once more to his first book, Manhood of Humanity, preparatory to publishing the second edition, reviewing and summarizing his life work, the importance of his new definition of man as the basis of his work began to loom larger than ever in his awareness. He had not stressed it for many years. ‘In 1921 the world was not prepared for it,’ he said. ‘It is more ready now. In a way I had to mature myself.’

Korzybski had learned continually from his students, and his confidence in the workability of his methods became strengthened. ‘I am the same kind of moron as the rest of you, it’ s the method that does the work, for me as well as you,’ he used to say. In his writings and conversations he continued to develop creative ramifications, yet circled closer to the core.

For some years his new introduction to the second edition of his first book had been postponed, because of the pressure of other work. During this time of intermittent writing on it, it remained a constant focus for him. He was analyzing the humanly disastrous effects of dictatorships in general, the evaluations of the people of the U.S.S.R. and their leaders in historical perspective, their socio-cultural milieu, some deeper aspects of symbolism, etc., in relation to the time-binding theory. There he also stressed the power of a theory as shown throughout history – in the realms of science, political science, religion, etc. – and the potential unifying, directive power of a theory as comprehensive as the General Theory of Time-binding. He found that each problem could be, and must be, reduced in its final analysis to the common root of misunderstandings. After over 25 years, he felt convinced once more, now with the conviction of maturity, that ‘we must first have a new notion of humanity.’

He also felt the need more strongly than ever for the ‘silence’, the quiet wide-eyed observing, with which he started his life, as an attitude essential for creative living. In 1948 he wrote, ‘There is a tremendous difference in “thinking” in verbal terms, and “contemplating”, inwardly silent, on non-verbal levels, and then searching for the proper structure of language to fit the supposedly discovered structure of the silent processes that modern science tries to find.'[1] In his last paper he was analyzing this attitude more in detail.[2]

This stressing of ‘inwardly silent contemplation’ seemed to grow out of his own hunger for close rapport on deeper levels with his environment, living or non-living. In whatever or whomever he observed, he ‘made the insignificant significant,’ and his comments were punctured and diffused with warmth of living values. He opened the doors of life and moved about freely, sensitively responding to the surrounding nuances – the feel of fine wood or of a precision cut steel tool, the look in one’s eyes, or the twist of a smile, the style of a man’s writing, the attitude behind the words, etc.

In his later years he had become more mellow, and he ‘was slowed down now by the heavy fatigue of constant pioneering struggle and the giving of himself. The injuries he sustained in the War grew increasingly difficult to cope with. He never lost his pithy unconventional humor, his eager interest in life and the urge – the necessity – to share it with others. He never ceased to care, and so he could not spare himself the suffering he felt when confronted by life’s daily tragedies, of small or large scope – some student’s trouble, or some disaster of historical import. Indeed, one may say that on 1 March 1950 his sudden death was characteristic of his life. But now, his organism could no longer handle the stress of his concern, and a coronary thrombosis was fatal.

Conclusion

Often Korzybski had mentioned his wish that his body should be made available for scientific study. This has been done and it may be of interest to quote here from a preliminary report by Dr. Nolan D.C. Lewis, Director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and Hospital. The friendship between Dr. Lewis and Korzybski began in the days when they were both doing research at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. At that time Korzybski watched Dr. Lewis perform many autopsies, and in planning for his own, had requested Dr. Lewis to do the autopsy and report his analysis. ‘The brain was unusually well preserved,’ Dr. Lewis has found. ‘It showed some of the normal shrinkage due to the age of the man, but it had a very rich blood supply which is significant and a complex convolutional arrangement which will be very important to study in detail, as it is the brain of a great scientist.’

Regarding his work Korzybski wrote in his last paper, in process of being completed at the time of his death: ‘There are many indications so far that the use of the extensional devices and even a partial “consciousness of abstracting” have potentialities for our general human endeavor to understand ourselves and others. The extent of the revision required if we are to follow through from the premises as previously’ stated, is not yet generally’ realized. Our old habits of evaluation, ingrained for centuries if not milleniums, must first be re-evaluated and brought up to date in accordance with modern knowledge.'[3]

While he had this large perspective, he remained keenly conscious of the limitations of his work, of himself as an individual, and of all humans. His theory of time-binding laid the embracing foundation for the study and realization of the potentialities of humans. ‘One of the key problems of my life work is that it is limited, limited,’ he said. ‘With the extensional devices you limit the seemingly unlimited.’

With a feeling that his formulations and methodological synthesis were but a part of the long processes of discovery of the natural laws of this universe, he was serene – the mysteries of life remain to be solved. ‘As to the space-time problem of the “beginning and the end of the world”, I have “solved” it for myself effectively by the conviction that we are not yet evolved enough and so mature enough as humans to be able to understand such problems at this date. In scientific practice, however, I would go on, in search for structure, asking “why” under consciously limited conditions,’ he wrote in his ‘credo’.[4]

He had a deep reverence for the methods of mathematics and the exact sciences, as expressions of human behavior in our general search for the structure of the unknown. He had a strong social feeling of responsibility in a personal, and a historical sense.

It may be said, perhaps, that Alfred Korzybski was very ‘Polish’: he was idealistic, yet practical, independent and staunch. He was unpretentious, lovable, earthy, vital, compelling, moved by a deep desire for feeling, knowing life, and around him there was a pervading warmth. He himself did not feel ‘Polish’ or ‘European’ or ‘American’; he had, rather, a feeling of belonging to the world-in-time. In the long time-binding sweep of human life, he has welded together past, present and future into a new form.

Footnotes

1. ‘What I Believe,’ in Manhood of Humanity, 2nd ed., 1950. International Non-aristotelian Library Publishing Company. Institute of General Semantics, distributors.

2. ‘The Role of Language in the Perceptual Processes.’ In Clinical Psychology Symposium on Perception: An Approach to Personality. To be published, Ronald Press, New York.

3. ‘The Role of Language in the Perceptual Processes.’ Op. cit.

4. ‘What I Believe.’ Op. cit.

Alfred Korzybski: A Memoir

by M. Kendig

Every scientific discovery is in a sense the autobiography of the man who made it.

Beginnings

Alfred Korzybski came to America in December 1915. He wrote Manhood of Humanity in 1920 when he was 41 years old. It is, so far as I know, his first written work published or unpublished in any language. To me this has always seemed a very significant thing, related to creativeness, the relentless vigor, the simplicity of the man, the integrity, the depth, the practicality of his work and methods. Over the years as I observed him and his method of work — visualizing, concretizing, slowly slowly bring the most complex problems down to their structural essentials in terms of simple earthy examples — I could well believe his report: “From babyhood I was silent, I had nothing to say.” — that is, before he came to America, made English his language, formulated his functional definition of man in this book. All his life he looked wide-eyed at the world, he contemplated what he saw, he questioned, why, how. He seemed possessed by a passion for comprehension. he lived and studied men on the soil of Poland, in the cities of Europe, on the battlefields of the eastern front. He studied the history of men, in books and at the universities — the successes and the tragedies of man-mad civilizations. He questioned why so? — how could we do better in our time? He was a lover of life, of music, of the poetry of feeling. He loved mathematics, engineering. They fitted the life facts. When men used them they escaped from animal trial and error, they could predict outcomes, pass on their findings, progress in their control of non-human things. Why was this not so in human affairs?

The impact of his experience in World War I, of coming to live in this new country and this open society, of finding a new language which suited him for the formulation of his non-verbal ‘thinking’ — these among others were precipitants. His lifetime studies and questions fell into new focus. He saw the significance of the obvious and the implications of the obvious. He verbalized the obvious in his functional definition of man as a time-binding class of life: Not what man is. What men do, as an exponential function of time. He developed the implications of the obvious characteristic of man and of man’s unique environments of symbolism and valuations, in Time-binding: The General Theory (1924-1926), in his Science and Sanity (1933), and on through to the end of his life in his later writings, in his seminars, and in his work with students.

This book [Manhood of Humanity (1950)] book has been out of print for eleven years. In these years Korzybski did his major teaching at the Institute of General Semantics, and Science and Sanity has been increasingly read, viz. twelve hundred copies bought from 1933 to 1938; seventeen thousand since. Very many who have read Science and Sanity and who have studied general semantics with him at the Institute have, I suspect, never held a copy of Manhood of Humanity in their hands. Science and Sanity, or someone else’s writings about general semantics has been their first introduction to Korzybski, and many have little notion what the term time-binding and its implications represent. Some of these persons have expressed in diverse ways vague discontent, an uneasiness as if they were missing something methodologically in the socio-cultural import which they felt but could not find made explicit in Science and Sanity. Korzybski was himself so full of the significance of time-binding, of the social feelings engendered by this new “image of man”, I do not believe that he saw this need until quite recent years. Meantime, requests for re-publication of his first book have been mounting steadily. He was meditating on a new introduction for over three years, and he was still working on it when he died. As the “Editor’s Note” indicates, plans for publication had been completed and this Second Edition must appear without his introduction. Fortunately, Korzybski’s own recent paper, “What I Believe” (1948), summarizes his life’s work, emphasizing the central role of his time-binding definition of man. This paper and Professor Keyser’s chapter on “Korzybski’s Concept of Man” (1922) were already planned for inclusion. They serve now as introductions, retrospective and contemporary, to this book. The editor, my friend and colleague Charlotte Schuchardt, has asked me to add some prefatory words before the volume goes to press.

Working with Alfred Korzybski

I knew and worked with Alfred Korzybski for fifteen years, first at a school where I was principal and then at the Institute he founded and which I am now privileged to carry on. I studied with him intensively and used his methodology at the school. He re-educated me as an educator, and I gained insights into multiple aspects of his life, his feelings and his methods. I also observed most of the 1800 who studied general semantics with him at the Institute seminars. Over the years, I came to feel that Alfred Korzybski, his life, his writings, the work he did, were singularly indivisible. In this brief memoir, I feel impelled to communicate something of that unique human-being-life-work complex, and to record an approach I have found clarifying in ‘seeing’ his work as a whole. In writing it, I have a picture of the potential readers of this book and tend to see them mostly as people who have read Science and Sanity and other writings dealing with general semantics per se. To convey briefly something of what I would like to convey to these readers, I must use Korzybskian formulations and terminology without explanation. For this I ask indulgence from other readers of the book.

This seems to me important: Korzybski’s time-binding definition makes a sharp distinction between men and animals. But he emphasized the differences without dismissing the similarities (not either-or)-without, that is, breaking the continuity of a dimensional hierarchy of life. Viewed on a scale of increasing orders of complexity, amoeba(1) …… Smith(1)-in-western-civilizationtoday represent natural phenomena; differ not in kind but in degree of complexity, the number of factors to be taken account of. With the time-binding theory, he made man and the accomplishments of men, the successes and the tragedies of human histories and cultures comprehensible. He reduced human phenomena to something already known, evident. He satisfied the creative scientist’s striving for unification and simplification of premises (i.e. Mach’s principle of economy). He formulated a basic theory for the foundations of a natural science of man, encompassing not only man’s biological but his psycho-symbolic nature, and his accomplishments (e.g. mathematics, the exact sciences, the arts, ethics, etc.). As a new theory must, time-binding covered all the old assumptions, included and explained new or neglected factors, led to the discovery of new factors, and their incorporation into that theory. The skeptic will question this. He may say this “is not science”, but a “miracle creed”. Admittedly so — perhaps. The values of a scientific theory, it seems, can only be assayed by what comes out of it by the process of ‘methodo-logic’ development, and by empiric demonstration of workability of principles and methods derived from it.

Formulation of the First Non-Aristotelian System

The theory of time-binding led Korzybski, inevitably, to the formulation of a first non-aristotelian system on premises of great simplicity, and to the formulation of a modus operandi for that system. This body of coordinated assumptions, doctrines, principles, etc., and methodological procedures and techniques for changing the structure of our neuro-symbolic reactions to fit an assumptive world of dynamic processes, he called General Semantics. He described this whole discipline as an empirical natural science and the extensional method as a generalization of the physico-mathematical ‘way of thinking’ applicable in all human evaluations.

For the rest of his life Korzybski was concerned with testing out the human values of his formulations, his hypotheses. Would the practice of general semantics liberate human time-binding energies, lead to more adequate evaluations, greater predictability and so sanity-in the lives of individuals, in their conduct of human affairs, and so eventually in the effects of science on society, narrowing the gap between these rates of progress?

Twelve years of study went into the formulations before he was ready to publish Science and Sanity. He studied human evaluations in science and mathematics and in psychiatry, “at their best and at their worst” as he put it, from the standpoint of predictability and human survival. He wrote the first draft of Science and Sanity in 1927-28. Published it in 1933 after tirelessly checking the data necessary for his methodological synthesis of modern sciences and testing the structural implications of the terminology in which he cast his formulations. As Poincaré said, “All the scientist creates in a fact is the language in which he enunciates it.” The changes Korzybski made in the verbalization of his formulations from his first book to Science and Sanity make a fascinating study in development of linguistic rigor. He called this testing of the structural implications of terms (and formulations) his “linguistic conscience”. Few know that Korzybski originally intended to call his major work Time-Binding. He changed the title to Science and Sanity practically on the eve of publication, because he felt he should emphasize that interrelation. The verbal continuity between Manhood and Science and Sanity he preserved in the title of Part VII, ‘On the Mechanisms of Time-Binding.’ In those pages, 369-561, he expounds his non-aristotelian system and general semantics. Many readers have apparently missed this continuity.

Science and Sanity

In this book, and in his early papers outlining the general theory of time-binding, the reader familiar with Science and Sanity can see and trace back the process of methodo-logic development from 1921 to 1933. He can see how the non-aristotelian system and general semantics followed from the theory of time-binding as inevitably as theorems from geometric postulates.(Note 1) He will see how the Structural Differential, the principle of consciousness of abstracting, the extensional method and devices, etc., came out of the theory and the related investigations of the mechanisms of time-binding. He will see, among others, the beginnings of Korzybski’s formulation of neuro-linguistic and neuro-semantic environments as the unique inescapable environment conditioning the reactions of the human-organism-as-a-whole, in any culture at any time-an invariant relation. This formulation of the neuro-linguistic and neuro-semantic environments (and the neurological mechanisms involved) seems to me one of the great and most useful of Korzybski’s higher order generalizations directly derived from time-binding theory. It generalizes to a higher order the “psycho-cultural approach” (Lawrence K. Frank, et al). It has made the mechanisms of cultural conditioning and cultural continuity comprehensible to me and many other students. It will, I believe, eventually unify and simplify the premises of cultural anthropology, psychiatry, Pavlovian and Lewinian psychology, empiric social sciences, etc.

The reader who has studied Science and Sanity, trained his nervous system with the techniques of the non-aristotelian discipline of general semantics, applied it in his life and work, has made his own non-verbal demonstration of empiric workability. He can assay the values great or small to him of what came out of Korzybski’s time-binding theory and compare his evaluations with the reports of others who, with various degrees of competence, have applied it in many fields.(Note 2) The reader who has merely read Science and Sanity, who ‘knows’ it verbally, even if he can repeat verbatim all the principles and terminology, has slight criteria for his evaluations. He may or may not get insights from the reports of others, i.e. accept their evaluations as shown in practice. If he enjoys skepticism he can argue as endlessly about the validity of the reports as he can about Korzybski’s theories, in the abstract. The aristotelian tradition has trained him to do that: words and experience are equated in the tacit assumption that if he knows the words he knows ‘all’; any proposition can be proved or disproved by talking, etc., etc. If he is trained in some scientific specialty, where he can, or thinks he can, narrow his problems down so that he has only two variables to control, he may balk at ‘accepting’ the empiric value of anything that deals with the multiple variables of human life and cannot be fitted into his formula.

Some have dismissed Korzybski’s work as “nothing new”. Others consider it “too radical” (or too “unscientific”) for serious “scientific consideration”. Such receptions of the new and different are not rare in the history of science. For ‘philosophic’ or ‘scientific’ skeptics who wished to argue a priori about his work, Korzybski had a favorite expression, “Don’t talk. Do it.” (“It is strictly empirical.”) This epitomizes the non-verbal character of the working mechanisms of the discipline, its strength-and the difficulties he faced in his pioneering efforts.

“I don’t know, let’s see!” was another pet saying of his, when faced with something new. This was the attitude he, the engineer, took toward his formulations. That is, he was his own best skeptic-he knew, for example, the pitfalls of ‘logical’ consistency versus life reactions. He remained ‘the skeptic’ for many years until he saw (had empiric evidence which satisfied him[*]) that the formulations, the verbal and non-verbal techniques of the extensional method he expounded and demonstrated in his seminars on general semantics were teachable and workable-were, in fact, an appropriate scientific methodology for the time-binding theory and for general education toward realizing human time-binding potentialities.

The Institute of General Semantics

Korzybski founded the Institute in June 1938. In September Chamberlain went to Munich. The words were “peace in our time” by “democratic appeasement”, and the facts were war and more dictatorships-as Korzybski sadly predicted in his seminar that autumn of ’38. His papers written during the next seven years record the impact on him, his reactions to World War II, in terms of his formulations and the direction his work was taking. Only those who knew and worked with him intimately know the depth of his social feelings, how he suffered in his whole person about the war. The daily chaos of today blunts our memories of what he-all of us have-lived through then.(Note 3)

He was 59 years old the summer he founded the Institute. The work he set himself to do there radically changed his life pattern. Behind him was a tremendous feat of physiological endurance, ‘mental’ power and vigor, the vast methodologic synthesis he had encompassed in Science and Sanity. The elegant simplicity of his formulations can be misleading in counting what they cost him as an organism. More feats of endurance were ahead of him. The new conditions were ill-suited to his make-up. Among others they deprived him of long periods of silence and isolation which were the sine qua non of his creative work, which he needed, craved as most of us do physical comforts. For the next eleven years he was surrounded by people and pressures. In the beginning he directed the Institute down to minutest details. He taught seminar courses and worked with individual students interminably. He carried on a mountainous correspondence. The number of papers he was able to write under the circumstances is remarkable to us who know the care he lavished on everything he wrote for publication. For many years he still hoped to write another book, incorporating the deductive presentation of the non-aristotelian system and general semantics which he made in his seminar courses. He was constantly harassed by our lack of money and security in carrying on the Institute and by the anomalies of a situation in which he could not approve or accept some well-intentioned suggestions and efforts made to help us gain acceptance and support. For example: Some wanted him to popularize his work, i.e. rewrite Science and Sanity for “the man in the street”, etc. Others wanted him to be less forthright in his presentations, to modify his theoretical position and so compromise with current academic and scientific orthodoxies to woo acceptance at the universities and support by the foundations. The price was too high for him to pay if it meant compromising the integrity of the discipline, and so eliminating the possibilities of demonstrating the human, scientific values of the general semantics methodology in clear-cut applications, and their eventual comparison with what was accomplished by prevailing methods. He had to continue to work beyond the institutional “safety zone”, although he was well aware of the disadvantages of doing so. Persons who themselves seemed unconcerned about the scientific integrity of the discipline, took easier paths and did not understand his position; labelled it ‘monomania’, ‘cultism’, ‘jealousy’, etc. This fretted and saddened him. To him, his position seemed as simple as saying, “Let’s stick to our premises. If we set out to solve a problem by non-euclidean geometry, we don’t switch to euclidean postulates. We would just make a mess. We have to have some honesty, stick to the method we start out with and then compare results. Which fits the facts best, which gives the most predictability in doing what we set out to do?”

The Institute was for Korzybski a training school and his research laboratory. He both taught and studied the students in his seminar courses. He was just as passionately absorbed in testing his work as he had been in formulating it. Each seminar meant 30 to 50 hours of vigorous lecturing, in some intensive courses eight hours a day. It meant hours of private work with each of the 40 to 50 students. He gave seminar after seminar, year after year. His endurance seemed endless. The results he saw in the lives and work of hundreds of these students and their reports to him over the years were not only his empiric evidence that his formulations did work. They were his chief source of happiness in the arduous Institute years.

He had his own peculiar style of lecturing, a nonlinear method of developing his exposition of non-aristotelian orientations by going round and round in widening circles, turning back to some example given at the beginning to illustrate a mechanism in his later lectures. He used shocking examples from his study in mental hospitals, from psychiatry, from his own experience with deeply maladjusted people, criminals, etc., to (as he called it) “get under the skins” of the class, to “shake them up”. He used examples from daily life, from the history of science, from mathematics. At times he was elegant, crisp, suave-at others, humorous and discursive. Often his face, his hands, conveyed as much as his words and diagrams. One educator said he was the “most powerful and effective teacher” he knew, “a master of pedagogy”. Another said he was “the worst, should study pedagogy”. People were seldom neutral about him, what he did, or how he did it. The more he shook their complacency, irritated them by “rubbing in” the method, the more they learned. He insisted that anyone who wished to, could enroll for a seminar. “Because a general method of evaluation,” he said, “has to work with anybody in any human activity or it’s no good.” Professors, doctors, psychiatrists, artists, researchers, young college students, businessmen, social workers, laborers, etc., all sat in the same classes. This may all sound chaotic; it was effective.

Korzybski's Students

In private interviews he showed individuals how to apply the methodology in analyzing and re-evaluating their personal lives and problems; he taught them to question their rationalizations, etc., constantly. These personal applications, he contended, must come first. The student must rigorously and continuously apply the extensional method in his personal living. Only then would he have a sure basis for successful application in handling ‘impersonal’ problems-the human relations, the methodological problems in his work in any field, whether science, art, medicine, education, business, etc. A psychiatrist said, “Korzybski deals with, uncovers ‘the cultural unconscious’, makes it ‘conscious’.[**] In psychotherapy we do the ‘same’ with the personal unconscious which is only a special case of the cultural.” Some like to call the seminars a “school of wisdom”. “Maybe,” said Korzybski, “but wisdom is not enough. There’s been plenty of wisdom in this world for millenniums and what? Wisdom, alone, doesn’t work. You have to have a method for applying it continuously.”

A significantly large number of those who studied with Korzybski in some 56 seminars benefited, continue to benefit, from the training in various degrees. He had his failures. “Ten percent of every class,” he claimed, “got nothing out of it.” “Some became,” he said, “my enemies for life.” (When you touch the fundamental verbalisms around which an individual has organized his life pattern, it may be too disturbing for him to face.) Some ‘got it’ quickly and as easily fell back into old habits of thinking-feeling. They use the words but not the method. “They ‘refused’ to work at themselves,” he said. Some learned general semantics ‘intellectually’ (i.e. verbally, ‘cortically’), knew all the principles and terminology and techniques, but simply could not apply them, change their evaluations, their living reactions. Some ‘got it’ very slowly, over the years. It apparently had no effect on their lives, their work, and then-something happened. Because to me it shows many things, I want to quote a letter written to Korzybski in April 1950 by a research psychiatrist who had not heard of his death:

Dear Count Alfred:

I think I owe you a little apology, a vote of thanks, and an explanation. As you recall it was in the summer of 1939 that I first became aware of General Semantics. At that time your and my good friend Dr. _______ [deceased] … took me with him to your Seminar. I could ‘get’ the cortical aspect [verbal] but for some reason the thalamic portion [change in living, feeling] seemed to elude me. However in this last month something apparently has happened. I begin now for the first time to ‘feel’ that General Semantics has something I need and which can help. What the explanation is I do not know-all I can give you is the answer my small son (thirty-four months) gives me-when I ask him why he does this or that, he simply says, “Well I did it” … just to let you know that sometimes it takes a little while for things to sink in, I remain,

Semantically yours

Korzybski held his last seminar December 27-January 4, 1950. That vast physiological endurance was running out. He no longer tramped up and down the platform waving his stick. His lecturing was as vigorous, his ‘thinking’ as creative as ever. In January and February he wrote his last scientific paper for the Clinical Psychology Symposium on Perception at the University of Texas.(Note 4)

Unfinished Work

The circumstances of his death, it so happened, were symbolic of his life and work. In working with students, he exhibited a tremendous power of caring about any individual bit of humanity before him. He was continuously aware that some infantile evaluation he might be struggling to change in an individual mirrored a symptom from the social syndrome. He spent the last few hours of his life at his desk working on such a problem. In his non-elementalistic orientation, the individual and society were split verbally only for convenience. Empirically, they could no more be split in the world of facts than space and time, psyche and soma, heredity and environment, etc. To him, no human problems were ‘insignificant’ problems. Thus the intensity, the warmth of his social feelings, the lavish extravagant ways he spent himself. He died March first at three o’clock in the morning. He had lived for 70 years, 7 months and 29 days.

In one way, we can say his work was ‘finished.’ In another hardly begun. For him it was finished in the sense that he had fulfilled the criteria he must have set himself after he had completed this book in 1921 from the point of view of theory, inductive and deductive methods, and empirical verification to a considerable degree (page xliv).